Inflation Targeting in the Time of Sanctions and Pandemic

ADNAN MAZAREI

I. OVERVIEW

High inflation is a growing economic and social problem in Iran under sanctions (Table, Figure1). The persistent trend contributes to a decline in living standards and increased income inequality. Inflation also hinders economic growth. A convergence of factors — budget deficits, rising partly due to harsh U.S. trade and financial sanctions, low oil revenues and the health and economic costs of the COVID-19 pandemic — will likely lead to greater easing of monetary conditions. If so, inflation will accelerate, resulting in more widespread social unrest. Iran lacks an effective anchor for inflation expectations.

The Central Bank of Iran (CBI) is muddling through in pursuit of a number of objectives. Those include lowering inflation; financing the public sector; allocating foreign exchange for import of essential goods; avoiding a sharp exchange rate depreciation; and preventing the banking system from slipping into protracted crisis. It uses a mix of tools, including quantity and interest rate controls on credit; direct lending to the public sector and banks; intervention in the interbank money market; and foreign exchange restriction and intervention.

While many inflation problems result from sanctions, economic institutions and monetary policies also play key roles. It is no surprise, therefore, that the CBI recently announced that it will alter its monetary policy framework to inflation targeting (IT) [1]. The increased emphasis on lowering inflation is welcome, but a key question looms: is IT the most suitable framework for lowering inflation in the near term? This paper examines whether the prerequisites for a successful shift in the monetary policy framework are in place; whether economic conditions will prevent successful adoption of IT; or whether a different monetary approach would yield better results until key reforms can be undertaken. The economy, languishing in deep recession, has contracted considerably for three years. Since the recession is due in part to supply shocks resulting from sanctions (and now the pandemic), monetary policy will not, in principle, be the most potent tool for fighting inflation. Very likely, the budget will remain the government’s main tool for combating the recession. Fiscal considerations are thus very likely to dominate monetary policy and undercut the CBI’s goal of lowering inflation from the current 27 percent to 22 percent by end-March 2021.

Successful IT requires meeting multiple conditions. Not all prerequisites need be fully in place at the start of a shift in monetary policy. Nevertheless, formidable economic and financial forces are arrayed to defeat efforts to establish an IT regime in the short term. Indeed, the CBI faces an almost impossible task given its limited independence, legally and practically, its inadequate credit and interest rate policies, difficult economic conditions and social and distributional pressures from various stakeholders. It will find it very difficult to credibly commit not only to a target under IT, but to any meaningful lowering of inflation under any alternative monetary policy framework. Important changes in the overall economic policymaking framework must be implemented, together with some easing of sanctions, before inflation can be lowered substantially. Adopting IT now, while helpful in pushing back against some of the government’s financing requests, could both be ineffective and lead to a further loss in CBI credibility.

In current circumstances, the introduction of IT may be at best an aspirational objective that can help the CBI focus more on inflation and establish prerequisite reforms in the future, especially once crippling sanctions are eased. For now, lowering inflation would require an agile and adaptive combination of fiscal policy, reduced focus on the exchange rate and more active use of interest rates, along with targeting of monetary aggregates. Sanctions problems aside, a more durable containment of inflation, including through IT, would require much lower fiscal dominance, a more independent CBI and corrections to acute banking system problems.

Section II examines whether the requirements for IT are currently met in Iran and whether factors such as sanctions prevent inflation reduction, including through IT. Section III discusses how the current deep recession and a recent surge in equity prices hinder the policy tightening needed for IT. Section IV suggests some preparatory steps that could help lay the basis for needed reforms.

II. DOES IRAN MEET THE PREREQUISITES FOR INFLATION TARGETING?

The key elements needed for successful IT are (1) CBI independence and freedom from fiscal dominance; (2) absence of external sector factors dominating monetary policy and preventing exchange rate flexibility; and (3) a healthy financial system that does not imperil financial stability, requiring the CBI to take actions that conflict with its inflation objective. In addition, the CBI needs well-developed data and analytical capabilities for forecasting inflation [3].

Fiscal dominance: CBI’s lack of independence and inability to control monetary conditions

Monetary authorities everywhere need to respond to fiscal pressures, but these should not dominate monetary policy decisions. Fiscal dominance — perhaps the main obstacle to IT — can be defined as the degree to which budgetary structure, policies and practices constrain monetary policy, thus limiting a central bank’s ability to pursue its objectives, among them managing inflation [4]. These constraints include the need to finance the public sector; the limits placed on a central bank’s policy choices and use of monetary policy instruments (especially with regard to credit policy and setting interest rates) to contain the costs of servicing the government’s debt; and quasi-fiscal operations.

Monetary policy and management in Iran have historically been heavily dominated by fiscal considerations in several ways that limit the scope and credibility to fight inflation (Figure 2). Arguably, the absence of independence and dominance of fiscal policy have been the most important constraints on CBI ability to lower inflation. Much of this fiscal dominance has been due to developments and policy decisions beyond the control of monetary policymakers, but much is also due to Iran’s institutional framework for economic policy [5].

First, the government exerts a direct role in determining monetary policy. For example, through its strong representation on the Monetary and Credit Council, it sets overall policies on sectoral credit creation and allocation (sometimes at subsidized rates). Monetary conditions are largely determined by the Council’s decisions concerning the amount of credit given by the banking system, rather than by the CBI [6].

Secondly, government revenues and expenditures have been closely linked, often procyclically, to oil and gas export earnings. In addition, movements in monetary aggregates have often been connected to fluctuations in oil revenues. There have been sporadic but not systematic efforts to sterilize the impact of oil export flows.

Thirdly, the CBI is involved in financing the government, as well as public sector enterprises and banks, in addition to undertaking quasi-fiscal operations. Though enjoined from direct budget financing, the CBI de facto helps finance the budget [7]. Furthermore, inflationary pressures are exacerbated by its purchases of foreign exchange from Iran’s sovereign wealth National Development Fund (NDF), in exchange for rials for transfer to the budget, which, once spent, increase the monetary base. Indirect lending has included providing resources to commercial banks to facilitate their lending to the government, as well as financing public enterprises. Therefore, assessing the impact of fiscal operations (by the government, NDF, public enterprises, and the semi-state entities) on monetary conditions must be done by examining the totality of these, at times, nontransparent transactions [8].

Furthermore, concerns about debt sustainability may increasingly constrain monetary policy. By the standards of emerging market countries, Iran’s central government gross debt is not very large. It was 40 percent of GDP in FY 2018/2019 and is projected to rise to 45 percent of GDP in 2020/2021 [9]. These figures, however, include neither government arrears nor the sizable contingent liabilities linked to the pension systems and the banking system’s capitalization needs. Once contingent liabilities are better taken into account, public debt sustainability could become a more important restriction on monetary policy. Accurate assessment of debt levels could necessitate generation of seigniorage revenues for the government or encourage inflation as an instrument for debt reduction. This could create further inflationary bias in central bank policy.

Looking ahead, therefore, fiscal pressures will inevitably dominate monetary policy. In light of sanctions that have sharply lowered oil exports, the contractionary economic impact of the pandemic and the limited scope for raising nonoil revenues, which are low by international standards, fiscal policy — especially expenditure policy — will remain the key economic policy tool [10]. Budget deficits will likely rise. In fact, the IMF projects that the budget deficit will go from 2.1 percent of GDP in 2018/2019 to 5.6 percent in 2019/2020 and 9.6 percent in 2020/2021.

Though the government aspires to cover its increasing financing needs by an enhanced program of selling treasury instruments and off-loading assets on the stock exchange, recourse to monetary financing and NDF resources (which raise the monetary base) will increase [11]. So long as the high degree of fiscal dominance continues, significant increases in interest rates could actually raise the risks of public debt becoming unsustainable [12].

External dominance: balance of payments crisis and exchange rate pressures hinder IT

Successful IT regimes rely, to different degrees, on exchange rate flexibility and attempt to contain the impact of exchange rate movements on inflation by actively managing interest rates. In Iran, which has experienced periods of severe depreciation, exchange rate movements have become a key driver of inflation and inflation expectations, affecting not only consumer and producer prices, but, increasingly, also asset prices.

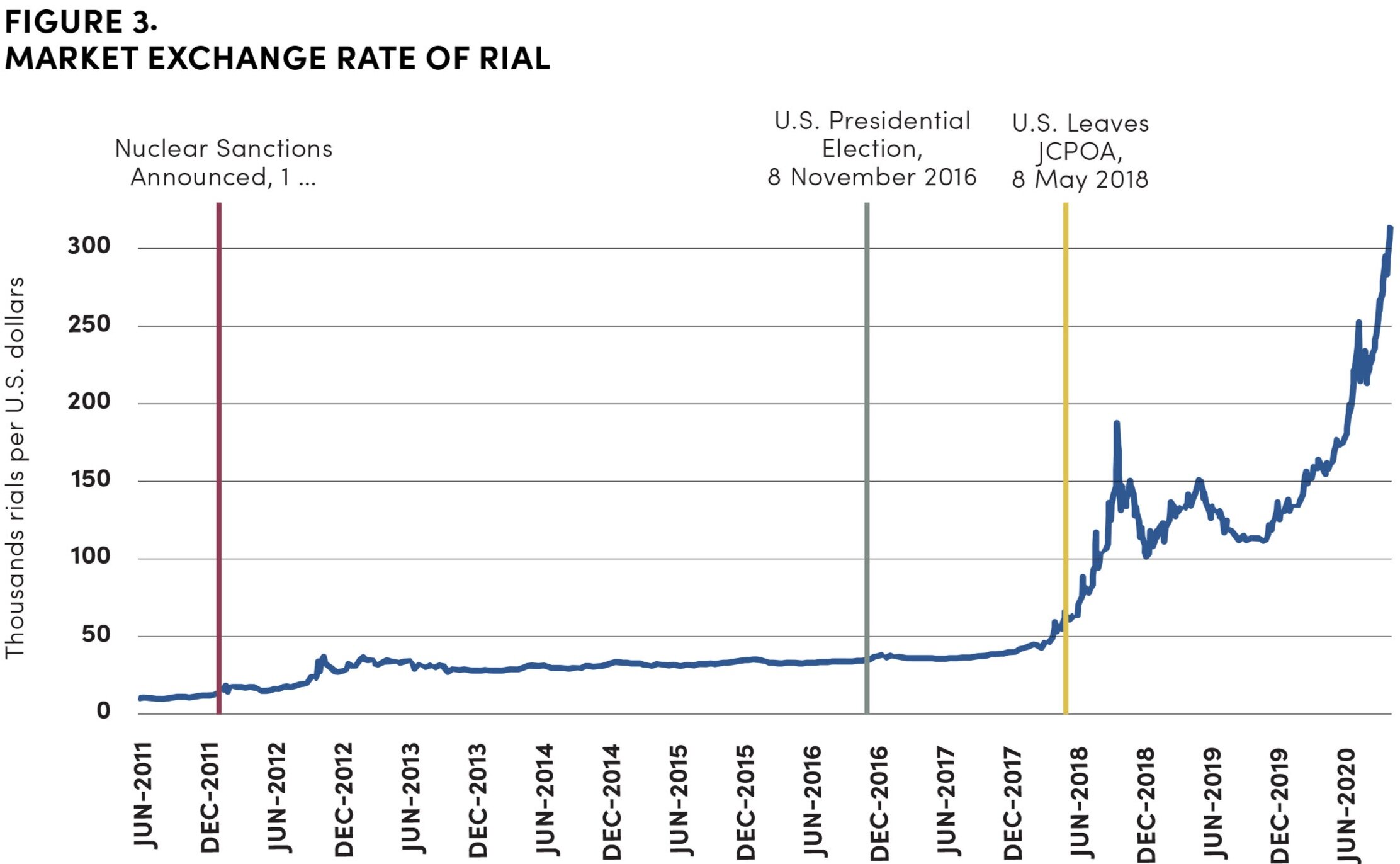

In recent years, Iran has experienced two major rounds of exchange rate depreciation, which, together with considerable growth in liquidity, have fed inflation (Figure 3) [13]. These depreciations occurred after imposition of sanctions by the U.S., UN and others in 2012 in connection with Iran’s nuclear program, and after the far more severe sanctions reimposed by the U.S. in 2018. These sanctions have led to sudden current account stops, as well as capital outflows [14].

Additionally, a sharp exchange rate depreciation occurred in 2020, because of the drop in global oil prices resulting from the pandemic and interruptions in international trade, as well as non-repatriation of proceeds on nonoil exports [15].

During those episodes, the CBI has tried to counter depreciation pressures through intervention in the foreign currency market, but has eventually yielded, resorting to a micro-managed multiple exchange rate system [16]. This approach was adopted largely because the CBI lacked independence to set exchange rate policy. Moreover, its ability to counter the impact of exchange rate depreciation by interest rate policy or foreign exchange intervention is much constrained. First and foremost, interest rates are not an active tool of monetary policy, as the CBI relies instead on deposit and loan rate ceilings and credit allocation directives. While the banking system legally operates under anti-usury Islamic banking principles, in practice it functions as a conventional banking system. Secondly, with much of its international reserves inaccessible due to sanctions, the ability to intervene in the foreign exchange market to smooth sharp exchange rate movements has become limited.

Financial sector dominance: banks are in a critical condition, forcing the CBI to focus on avoiding a banking crisis at the expense of higher inflation

The banking system is unsound. Its grave condition makes Iran highly vulnerable to a financial crisis. Fear of destabilizing the banking system is a major constraint on CBI ability to contain the growth of monetary aggregates and inflation.

First, the banking system suffers from weak balance sheets. While reliable estimates of nonperforming loans (NPLs) are not available, estimates range from 11 to 50 percent. Moreover, loan provisioning is low, and many banks have accumulated sizable losses [17].

Secondly, commercial banks have often faced significant liquidity shortages, prompting them to borrow from the CBI and to compete with one another by offering higher interest rates [18]. In recent years, the CBI has been the lender of first resort for commercial banks, which have met liquidity needs by borrowing from its discount window at high interest rates, without collateral [19]. Massive borrowing has made banks one of the largest sources of growth in base money [20]. Given the structural factors behind their balance sheet problems and the scale of those difficulties, banks will likely remain substantially dependent on CBI support. Monetary policy is thus also expected to remain significantly dominated by banking sector conditions.

The banking sector problems result from (1) pervasive state ownership and control over the banking system, leading to noncommercial and directed lending to government and public enterprises; (2) banks’ association with conglomerates of public and private firms that own equity in them, or have equity holding in some firms; (3) weak prudential regulations (eg, capital adequacy, classification, provisioning and exposure limits) and lack of enforcement; (4) interest rate controls by the CBI that have often led to negative real interest rates and financial disintermediation; and (5) poor governance and corruption (Figure 4) [21].

Moreover, much of the banking system’s difficulty can be traced to external sanctions, which, in addition to inflicting severe economic damage on the overall economy and banks’ asset quality, have effectively cut off the banking sector from the global financial system.

The pandemic has exacerbated the challenges afflicting Iranian banks, affecting economic activity and potentially raising the proportion of NPLs. Balance sheets are expected to be damaged, at least short-term, from CBI measures taken to allay pressures on borrowers. For example, the CBI asked commercial banks to postpone repayment of loans due in February 2020 for three months and offered temporary penalty waivers for customers with NPLs [22].

Putting the financial system on a sound basis is necessary for lowering banks’ reliance on the CBI and strengthening the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Yet, none of the banks’ difficulties are expected to diminish soon; nor will the underlying factors be corrected quickly. Monetary policy will continue to focus to a great extent on preventing banking system collapse, including by averting bank runs. Reforming the sector will be complex, requiring important changes to fundamental aspects of economic governance. Reforms must include overhaul of the state’s role in banking system ownership and the undertaking of quasi-fiscal tasks by banks; banks’ participation in conglomerates owned by large holding companies; banks’ ownership of firms and participation in noncore banking activities; improved governance of corporations; a review of banks’ assets; and better supervision and enforcement by the CBI.

Comprehensive restructuring and resolution of banks will inevitably require their sizable recapitalization using budgetary resources. It will also involve closings and mergers of banks; clearing of public sector arrears to banks; systematic review of the quality of banks’ assets; and perhaps establishing asset management companies to resolve their nonperforming assets. An overhaul of regulations governing the CBI (including its functions as lender of last resort) and the banking system will also be needed. These are daunting but imperative tasks, needed to control inflation and allow better provision of credit to tradable goods sectors that could expand due to recent depreciation of the real exchange rate.

Data and Analytical Capabilities

Another, perhaps secondary, IT success requirement is availability of reliable data and analytic capacity for forecasting inflation. There are significant shortcomings, principally regarding fiscal and monetary data that undermine credibility, particularly in an IT regime. Fiscal data are inadequate in multiple categories: operations of public enterprises, off-budget transactions and quasi-fiscal operations by the CBI, public banks and quasi-public institutions. In addition, monetary data are published only after long delays and are at times difficult to interpret, given ad hoc transactions. The occasional reclassifications of CBI claims on public enterprises, recategorized retroactively as claims on the government, are an example of the latter.

External sanctions also affect the quality and timeliness of data. Data on Iran’s international reserves and their usability are limited. This constrains analysis of developments in the foreign exchange market and hinders economic agents’ ability to track and understand economic trends. Through its Money and Banking Research Institute, the CBI does perhaps have the technical abilities for modeling and forecasting inflation. However, any move to an IT regime will entail shifts in the monetary regime and the transmission channels of monetary policy to the economy. A change of this magnitude will require new empirical work.

III. IT CHALLENGES AMID DEEP RECESSION AND SURGING ASSET PRICES

Conjunctural factors also limit, but do not make it impossible, for the CBI to tighten monetary conditions sufficiently to reduce inflation and reach its inflation target. These factors include the recession and the recent spectacular increase in equity prices.

The deep recession is a constraint on monetary tightening

Iran’s economy has been contracting sharply. The IMF expects real GDP to shrink 6 percent in fiscal year 2020/2021, leading to an 18 percent drop in the three years following U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal and reimposition of sanctions (Figure 5). Matters could worsen if the pandemic’s second wave becomes more severe, further limiting mobility. Public and private sectors will continue to rely on bank financing, hampering efforts to curb inflation.

The private sector relies on banks mainly for financing current operations, thus limiting the scope for tightening of monetary conditions needed to lower inflation and support IT.

A key channel between monetary conditions and economic activity is through provision of working capital to firms. Iran’s corporations cite access to finance as a key constraint to operations. With capital markets inadequately developed, firms rely on bank credit, including mainly for working capital. During April-November 2019, more than a half of borrowing was for working capital, particularly in the industrial and mining sectors.

The supply of working capital has seen sizable fluctuations, particularly when draconian external sanctions were imposed in 2012 and 2018. Banks were hindered in shifting resources among firms and helping businesses cope with sanctions [23]. Figure 6 shows the fluctuations in lending to firms in real terms (deflated by the producers’ price index) [24]. Helping banks meet firms’ demand for working capital will likely remain a constraint, impeding the CBI’s its shift to an IT regime.

Fear of bursting euphoric stock prices also restrains monetary policy

For two years, monetary policy actions have been needed but not taken to contain the huge surge in asset (especially equity) prices that are difficult to justify in terms of fundamentals. Given high inflation and negative interest rates, there has been an increasing shift in resources to asset markets, foreign exchange, gold, real estate and equities.

Despite the recession, which has weakened the fundamentals that ultimately underpin equity prices, the Tehran stock exchange has risen by 296 per cent in nominal terms between 1 January and 3 October 2020, far above inflation or market exchange rates (Figure 7). Heavily influenced by a shortage of inflation hedges, the rush to equities involves both institutional and individual investors. Some of the equity price surge is justified by the higher earning potential of producers of tradable goods on account of the real depreciation of the rial. These factors aside, however, there may be a growing disconnect between the huge increases and the economy’s fundamentals.

Despite the euphoria, there is a risk of a sizable equity price correction. There is also awareness of the possibility that, had it not been for the climb in stock prices, there might have been even greater exchange rate depreciation and consumer price inflation. Furthermore, the boom in equities is perceived as helping government efforts to finance its budget deficit by selling assets on the stock market [25]. These factors, together with its lack of independence, have thus far prevented the CBI from taking needed steps, including raising interest rates, to contain the rise of stock prices. They have also impeded monetary policy actions to reduce inflation. As a corollary, the CBI has lessened chances for successful IT implementation.

IV. THE ROAD AHEAD

The path to an IT regime

Containing inflation is critical for Iran’s economic and social stability. Achieving price stability on a durable basis requires (1) that the CBI be provided with a clear and flexible IT mandate and the operational independence to deliver on it, but also be held accountable for achieving the inflation target; [26] (2) granting the CBI more independence and lowering fiscal dominance significantly; (3) unifying the multiple exchange rates, shifting to a more flexible exchange rate regime and ending micromanagement of the foreign exchange market; (4) taking necessary steps to correct major banking system problems; (5) developing effective instruments for monetary control (eg, a deep bond market); and importantly (6) an easing of external sanctions. Greater efforts would also be needed to bolster CBI technical capabilities, especially in data dissemination and inflation forecasting. In fact, most of these are required also for any successful effort to lower the endemic inflation problems.

Though not everything must be done up front, meeting the requirements and operational aspects for shifting to IT is politically and technically difficult for any developing or emerging market economy. In Iran, whose economy and finances are so subject to political and other domestic impediments, especially the absence of CBI operational independence and the dominance of fiscal policy, external factors, importantly sanctions and vulnerability to a financial sector crisis, will likely prevent the near-term success of an IT regime.

What can be done now?

In the short run, theoretically the CBI could (1) continue the status quo, pursuing multiple objectives and ineffective instruments; (2) muddle through with an inflation objective, perhaps framed initially simply as moving toward containment but without committing to a specific target; (3) commit to a fixed monetary growth path — difficult given government’s rising financing needs and in the event of a deeper banking crisis; or (4) pursue an exchange rate peg, or crawling peg, which is very difficult in the midst of a balance of payments crisis.

Continuing with the status quo is highly undesirable since it would likely lead to higher inflation. Credible adoption of options 2-4 would require eliminating fiscal dominance and considerable easing of sanctions. Option 2 might be the best possible in current circumstances. With a balance of payments crisis and deep economic recession, lowering inflation would require a nimble, adaptive combination of fiscal policy (including cutting unproductive spending and shifting resources toward such priorities as health and protection of the unemployed and vulnerable); greater exchange rate flexibility and monetary management (with more active use of interest rates, targeting of monetary aggregates, macroprudential tools and eliminating an unrealistically fixed official exchange rate); and incomes policies (eg, direct income supports). Simple methods of anchoring inflation by managing the exchange rate or targeting the growth rate of a particular monetary aggregate would very likely fail. A more eclectic approach might help the CBI move toward a framework to manage inflation expectation and set inflation trends on a gradually declining trajectory, aided by a more active interest rate policy.

Arguably, Iran does not now meet the requirements for IT, especially freedom from fiscal dominance, eliminating which requires important political and institutional changes. But the economic crisis offers both opportunity and incentives to take preparatory steps. These could include (1) improving the quality and timely dissemination of statistics; (2) upgrading the functioning of the government securities market to facilitate open operations; (3) securitizing the arrears of the government and public enterprises to the CBI and banks; and (4) containing expansion in bank balance sheets. While it may be premature to resort to IT for taming inflation, that objective could be instrumental in establishing a basis for needed reforms.

ENDNOTES

The CBI has also taken steps to improve its monetary policy tools, including strengthening its ability to perform open market operations. It also intends to undertake a reform of the currency by dropping four zeros.

Based on Iranian fiscal years, which run from 21 March to 20 March.

See Rashad Ahamed, Joshua Aizenman and Yothin Jinjarak, “Inflation and Exchange Rate Targeting Challenges under Fiscal Dominance,” NBER Working Paper (2004); IMF, “Inflation Targeting and the IMF.” Policy Paper (2006); and Edwin Truman, “Inflation Targeting in the World Economy, Challenges and Opportunities”, Peterson Institute for International Economics (2003). The conditions discussed correspond with those used by Arminio Fraga, Ilan Goldfajn, and Andre Minella, “Inflation Targeting in Emerging Market Economies,” NBER Working Paper (2003).

The CBI has little de jure independence to decide objectives or the instruments to pursue them. The parliament (Majlis) has long had before it a draft central bank law to bolster its inflation focus, but there has been little progress. [numbering]

One example of factors beyond the control of the CBI (and the government and parliament) is the ability of the country’s leadership to overrule budget decisions. An example was the role of the supreme leader in determining the outcome of the most recent budget discussions, by taking the decision power away

from the parliament.IMF, “Islamic Republic of Iran: Selected Issues,” Country Report No. 17/63 (2017). The CBI has over time acted to affect monetary conditions through market-based tools, including an inter-bank market, repo and swap facilities, and a corridor system for the interbank interest rate.

The government is not permitted to borrow from the CBI, except within a fiscal year, mainly through a revolving fund. Any outstanding amount must be repaid at the end of the fiscal year. In practice, however, as evidenced by the data on CBI lending to the government, this constraint is not respected.

Another factor complicating analysis of the links between fiscal developments and monetary conditions is the prevalence of government arrears to the CBI, commercial banks and various enterprises. These are occasionally cleared through netting operations or by formally acknowledging them as government debt, making analysis of monetary policy difficult. For example, much of the jump in public debt from 11.8 percent of GDP in FY 2014/2015 to 22.3 per cent in FY 2015/2016 was due to reclassification of government arrears as public debt proper. Iranian fiscal years run from 21 March to 20 March.

9. MF, “Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia,” (October 2020).

10. Central government nonoil revenues averaged 11.8 percent of GDP during 2017-2019, ibid.

11. Unlike many other emerging market countries, however, Iran’s external debt, at about 3 percent of GDP, is a negligible constraint on the conduct of monetary policy.

12. Higher nominal interest rates can lead to higher (rather than lower) inflation when IT is combined with fiscal dominance. See https://bfi.uchicago.edu/ wp-content/uploads/Leeper-Leith-Handbook-Jan2016-Final.pdf. Of course, this effect could also happen without fiscal dominance, to the extent that the government borrows significantly from the commercial banking system, thus raising interest rates.

13. For examples of empirical work on inflation determinants, including the pass-through from exchange rate movements to inflation, see IMF (2017), op. cit., which found a pass-through of 44 percent from January 2012 through June 2016.

14. Given the real depreciation of the rial, nonoil exports have received a major boost, but with shortfalls in repatriation of the export proceeds, they have not been able to compensate for the decline in oil prices.

15. Given depreciation of the real rial exchange rate, nonoil exports have received a major boost, but with shortfalls in repatriation of the export proceeds, they have not been able to compensate for the decline in oil prices.

16. Iran now has a system of three exchange rates: (1) a fixed official rate for importing essential goods; (2) a flexible rate determined by exporters of non-oil products and importers (set on the foreign exchange platform NIMA, which has been in operation since April 2018); and (3) a flexible rate set by money changers (the free market rate). In September 2020, while the fixed exchange rate stood at 42,000 rials per dollar, the NIMA and the free market rate were, respectively, on average 215,000, and 268,000 rials per U.S. dollar.

17. Adnan Mazarei, “Iran Has a Slow Motion Banking Crisis,” Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief 19-8 (2019). The latest information available put loan provisioning at 4.9 percent of risk-weighted assets in June. IMF, “Islamic Republic of Iran — Staff Report for the 2018 Article IV Consultation.” Banks also have some “frozen assets”: collateral seized from delinquent borrowers; their own investments in real estate (which may not be marked to market); and unprofitable state-owned enterprises given to banks by the government to settle its debt to them.

18. Until recently, banks also had to compete for funds with unlicensed financial institutions not subject to the CBI’s interest rate ceilings; these institutions are now under more regulatory oversight; several have been closed, and a few have been merged into the regulated banking system.

19. The CBI has recently resumed efforts to ensure that banks collateralize borrowings from it by using government bonds.

20. The CBI provides banks liquidity support directly through its emergency window and indirectly through the interbank market, where it lends to some state-owned banks to be on-lent to other banks. The CBI has usually lent through its emergency window without collateral, but it has recently taken steps to require banks to present government paper as collateral. The trend in banks borrowing from the CBI appears to have slowed in 2019. But closer examination shows that the decline may be due to balance sheet changes that shifted some claims on public sector banks (and on some public enterprises) to claims on the government.

21. The CBI sets maximum deposit and lending rates, but some banks have at times circumvented those rates.

22. Banks’ compliance with these CBI initiatives has been limited. In fact, in many instances, banks have taken advantage of payment delays by borrowers to collect on their collateral.

23. The episodes covered by sanctions are also those when firms are under pressure to show forbearance to clients who have difficulty meeting their financial obligations, raising their demand for bank credit.

24. Firms’ dependence on banks for working capital has been a continuing policy debate topic. Farhad Nili and Amineh Mahmoudzadeh, “The Structure of Firms’ Costs and Demand for Financial Resources” (in Persian), Monetary and Banking Research Institute Policy Note (2015); Imam Soukhakian and Mehdi Khodakarami, “Working Capital Management, Firm Performance and Macroeconomic Factors: Evidence from Iran,” Cogent Business and Management (2019) 6: 1-24. It recently induced the CBI to put in place a new facility (GAM) to help meet firms’ working capital needs.

25. The desire to prop up stock prices to help government sell its assets on the stock market and avoid other disruptions went into high gear after those prices dropped about 25 percent in August-September 2020. The authorities are using NDF resources to support stock prices and allowing commercial banks to buy them.

26. Flexible IT would entail not only paying attention to the output gap and using interest rates actively, but also exchange rate intervention, especially to address fluctuations in oil revenues, including to create appropriate incentives for economic diversification in the face of weakening prospects in the oil markets. For a discussion of the problems of applying narrowly defined IT in commodity exporting countries, see Jeffrey Frankel, “Monetary Regimes to Cope with Volatile Commodity Export Prices: Two Proposals,” in Rabah Arezki, Raouf Boucekkine, Jeffrey Frankel, Mohammed Laksaci, and Rick van der Ploeg (eds.), Rethinking the Macroeconomics of Resource-Rich Countries (London, 2018).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adnan Mazarei joined the Peterson Institute for International Economics as a nonresident senior fellow in January 2019. His work at the Institute focuses on the major economies of the Middle East and Central Asia and the long-term financial and macroeconomic challenges they face.

Previously he was a deputy director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), where he worked on resolving various financial crises in emerging markets, including the 1998 Russian financial crisis. In addition, he contributed to the IMF’s policy work on international financial architecture and sovereign debt issues. He helped prepare the Santiago Principles that established best practices and guidelines for managing sovereign wealth funds. Between 2002 and 2005, he served as advisor to IMF management.

More recently, Mazarei helped manage the IMF’s strategy and global coordination of the support for the Arab Spring countries and for the economic policy response to the recent conflicts and refugee crisis in the Middle East.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I am grateful to Ali Vaez, visiting fellow at the Foreign Policy Institute of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, for managing this project. I have benefitted from comments from Jihad Alwazir, Andy Berg, Kathleen Burke, Shahrokh Fardoust, Joseph Gagnon, and Patrick Honohan. I am particularly grateful to Razieh Zahedi for her comments on earlier drafts of the paper and for helping me with the data. - Adnan Mazarei

The SAIS Initiative for Research on Contemporary Iran

Johns Hopkins University Washington, DC

Copyright 2020 All rights reserved