The Experience of Iran’s Manufacturing Sector Under International Economic Sanctions

HADI SALEHI ESFAHANI

ABSTRACT

This study examines the experience of Iran’s manufacturing firms in the past 15 years when the country was under international sanctions with various degrees of intensity. Contrasting the sector’s trends during two episodes of major intensification in 2012-2013 and 2018-2020 with the years preceding them suggests that by restricting access to global credit, technology, and product markets sanctions squeezed many firms on both supply and demand sides and slashed their productivity, though the effects were far from uniform. Some industries that depended on imported inputs and foreign technology were generally hit hard, while some others that relied more on the country’s own resources and regional export markets gained from a demand shift toward domestic products. These changes have been associated with enormous movements in relative prices. The rial depreciated significantly, producer prices rose, and real wages tumbled each time sanctions intensified. This encouraged employment despite initial shrinkage of output and declining investment. The result was job creation without growth, in sharp contrast with a jobless growth process that had prevailed in manufacturing before 2012. The data show that entry and exit of firms did not play a significant role in this shift. Rather, mostly exiting firms seem to have adjusted to the shocks and learned to survive.

I. INTRODUCTION

While international economic sanctions are being increasingly used to achieve foreign policy goals, little is known about their impacts, and their effectiveness is hotly debated [1]. They may impose huge costs on groups that are not the intended targets and may even benefit some groups that are meant to be hurt. Complexity regarding their effects is particularly notable in the case of impacts on firms. Since sanctions typically impede target-country firms’ access to international finance, technology and imports, it is natural to expect their production costs to rise and outputs to decline. Firms are also likely to be negatively affected on the demand side, as export opportunities are restricted and darkening economic prospects reduce investment as well as household incomes and expenditures. Whether the tightening constraints are on the supply side or the demand side, or maybe both, many firms are likely to end up producing at a reduced scale, which could raise the per unit production costs and compound the problems in industries with economies of scale. However, for some industries and firms, the restrictions on imports may counteract with these tendencies as import limitations shift the demand toward domestic producers of import substitutes, thus helping some firms to expand while others are contracting. Similarly, sanctions are likely to induce substantial currency depreciation, which could encourage production of exportables and import-competing products. The situation could get further complicated by the nature of the government’s responses. As a result, the overall impact of international sanctions may vary across industries and firms. Hence, understanding the outcomes requires careful examination of the specific circumstances.

This study seeks to shed light on the experience of Iran’s manufacturing firms in the past 15 years as economic sanctions intensified with ebbs and flows. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the UN Security Council passed a number of resolutions that envisioned increasingly severe sanctions on Iran. These sanctions ultimately went into full effect in 2012-2013. The situation eased somewhat in 2014 and 2015 as Iran engaged in negotiations with the 5+1 group of countries, consisting of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany together with the European Union. Further relief from sanctions came in 2016 after the negotiations yielded a “nuclear deal,” the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). However, the sanctions returned with greater intensity in 2018 when U.S. withdrew from JCPOA and added new and more severe measures. These variations provide some opportunity to explore how sanctions may have affected the performance of manufacturing firms in Iran. In this study, we will pay particular attention to the 2012-2013 episode of sanctions intensification since much more data is available for 2005-2013 period than for the years since then. Of course, sanctions are not the only factor that has affected the manufacturing sector over the past 15 years, and it is not easy to distinguish the degree of causality attributable to sanctions vs. many other domestic and international factors that may have been consequential for the sector. The aim here is to examine the changes in the sector’s performance as sanctions’ intensity changed and suggest possible connections, while keeping in mind that some changes could be due, partly or totally, to other factors. A similar problem exists in establishing the exact channels of influence from sanctions to firm performance in different industries.

Most papers in the literature concern sanctions’ costs, effectiveness and efficiency, asking whether they impose large costs on particular industries or on target groups of decision-makers while minimizing the negative impact on the rest of the population. A paper by Felbermayr et al. is a recent example of such studies [2]. That study first estimates a structural gravity model of trade to measure the impact of sanctions on Iran’s trade flows. It then uses a simulation exercise to infer the extent to which value added in each industry must have been affected by sanctions. Its simulation suggests that the costs must have been substantial, especially in industries where Iran has comparative advantage. However, the exercise does not seem to generate reliable estimates, because it does not use the actual value added realizations under sanctions [3]. Two other recent studies examine the impact of sanctions on the stock returns of Iranian firms listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange [4]. They find that the news about changes in sanctions affect the returns of all listed firms, but more strongly those in Iran’s “semi-state” sector [5]. This, of course, does not prove that the sanctions were targeted at the semistate firms, since such firms may be concentrated in some industries that happen to be more vulnerable [6]. Also, the studies overlook other factors that may have affected the returns, such as alternative investment platforms to the stock exchange and legal and political developments affecting various companies, etc.

This study focuses on the broader effects of variations in the intensity of sanctions on manufacturing industries, rather than on particular firms [7]. It addresses questions such as: how Iran’s manufacturing firms have fared under the past and current rounds of sanctions; how sanctions have affected employment, production, capital formation, productivity and imports and exports of manufacturing firms; how prices and wages have responded to the shocks; which industries and types of firms have been hurt by sanctions and which have fared relatively better; and whether government policies have helped or harmed the situation.

Section II examines the changes in the aggregate trends of the manufacturing sector since the mid-2000s, as the intensity of sanctions changed. Section III analyzes the role of entry and exit in the performance of firms during the 2012-2013 intensified sanctions episode. Section IV explores sanctions’ differential impacts on various manufacturing industries. Section V discusses the changes in firms’ scale of production under intensified sanctions and derives implications for firm performance. Section VI provides a brief conclusion.

II. SANCTIONS AND THE AGGREGATE TRENDS IN THE MANUFACTURING SECTOR

After an overview of the overall sector trends, using aggregate data from the Central Bank of Iran (CBI), micro data on manufacturing firms with ten or more workers from the Survey of Manufacturing Firms (SMF) of the Statistical Center of Iran (SCI) is used to explore trends in more detail [8]. This data set is available only from 2003 to 2013, so can be used only for analyzing the 2012-2013 sanctions episode [9].

Between mid-2004 and mid-2012, manufacturing sector value added experienced relatively high growth, except for a brief slowdown in 2008 (Table 1 and Figure 1). Indeed, the growth rate was notably faster than that of non-oil GDP during the same period (an annual average rate of about 6.5 percent vs. 4.9 percent). This trend seems to have been associated with growth in real investment, non-oil exports and private consumption (Figures 1 and 2). Real imports were also generally rising until the end of 2010, but started a precipitous decline in 2011 that lasted until 2016 (Figure 2). The manufacturing sector’s growth started to slow in 2011, then nosedived in mid-2012 as sanctions intensified. The 2011 slowdown and import contraction may have been in anticipation of tighter sanctions, as the UN was taking tougher stances against Iran. However, they were also associated with reduced government expenditure (possibly an effort to control inflation) and a major subsidy reform at the end of 2010 that significantly increased energy prices. The demand for manufacturing seems to have further softened in 2011 and most of 2012 as a result of stagnation in non-oil exports, which was probably due to currency overvaluation (Figure 5). This changed in 2012, when the currency lost about half its real value against the U.S. dollar, as sanctions intensified and oil exports were cut sharply. In response, non-oil exports expanded rapidly, while imports continued a steep decline.

A notable feature of the trends in manufacturing activity was the rapid fall in employment between the mid-2000s and early 2010s, before sanctions’ 2012 intensification, which contrasted with the growth of the sector’s value added (Figure 3). This meant that labor productivity (i.e., value added per worker) rose rapidly in that period. As Figure 4 shows, this trend was not generally associated with an increase in total factor productivity (TFP). So, other factors must have driven the combination of value-added growth and diminishing workforce. Among these, two factors seem quite notable: a very low cost of capital and rapidly rising real product wages (Figures 5 and 6), which encouraged growth through substitution of capital for labor [10]. Both factors were at least in part due to the CBI policy of keeping the nominal exchange rate stable in the face of rising non-tradables’ prices. This made import prices, including those of capital and intermediate goods, relatively cheap and put downward pressure on the domestic producer prices of tradables, allowing wages and non-tradable prices to rise relative to the average price level [11]. A number of other government policies also contributed to the low cost of capital (eg, highly subsidized credit) and high wages (eg, rising wages in development projects). Of course, the decline in producer prices of manufactured goods, which are generally tradable, relative to the non-tradable prices must have discouraged domestic production activity. However, the lowered cost of capital and imported material counteracted with that effect and induced an investment boom, as seen below.

The indices of real wages in the government’s development projects depicted in Figure 5 indicate that relative wage trends started to reverse in 2009 and dropped precipitously in 2010-2011, before intensified sanctions were applied in 2012 [12]. However, the average manufacturing real wage index derived from the SMF dataset (Figure 6) suggests that the reversal came somewhat later, and the steep drop coincided with the tightening of sanctions in 2012. This discrepancy between the indices in Figures 5 and 6 seems due to the government’s attempt to control inflation by applying breaks on wage growth for workers in its projects. The average manufacturing real wage appears to have continued to grow in 2010, to drop somewhat in 2011 as producer price inflation accelerated, and then to be hit hard in 2012 by the rial’s depreciation and the jump in product prices [13]. The downward trend in this index continued in 2013, though at a somewhat slower pace. The real wage rates in government projects, on the other hand, stayed rather steady until 2014, after which they rose. We lack data on manufacturing wages after 2013, and they may have behaved differently than government project wages in recent years. However, it is likely that the two series have moved in the same direction over longer terms, as they did in the 2000s. Therefore, the latter indices are used to come up with conjectures about manufacturing wage trends since 2014.

The contractions in imports and manu- facturing output under intensified sanc- tions continued until early 2014, when they bounced back briefly. The total decline in the rolling four-quarter value added of manufacturing from its peak in 2012 (Q2) to its trough in 2014 (Q1) was 9.7 percent. For real imports, the corresponding decline was 29.2 percent. Meanwhile, non-oil GDP experienced more a stagnation than a dip (Figure 1), as agriculture and services continued to grow. Both supply and demand shocks are likely to have contributed to the drop in manufacturing activity. On the demand side, there were sharp declines in public consumption and investment, which mattered much more for manufacturing than other sectors, but, there was some compensation by the expansion in non-oil exports [14]. The considerable reduction in imports must have also shifted the aggregate demand toward domestic products, but the rise of imported input costs is likely to have counteracted with that effect, discouraging production. The SMF dataset indicates that, between 2010 and 2012, the real value of imported inputs for manufacturing establishments with ten or more workers fell by some 40 percent — much larger than the drop in total imports during the same period. Under these circumstances, aggregate TFP dropped sharply by about a third from 2011 to 2013 (Figure 4), compounding the other supply and demand shocks. This issue is discussed further in Section V below.

The short-lived recovery in manufacturing value added in 2014 (8 percent growth) took place, aided by increases in all components of demand, as Iran negotiated with the 5+1 group to remove UN sanctions. Meanwhile, the pre-2011 pattern of wage and price movements returned: The rial began to appreciate, relative producer prices declined, and real wages rebounded.

Despite expectations of sanctions relief, manufacturing production fell in 2015. This was most likely due to a sharp drop in oil prices in world markets, associated with restraint in government expenditure and other components of demand, except non-oil exports. However, after the JCPOA went into effect, manufacturing growth resumed in 2016-2017 at an annual rate of about 6 percent (Table 1). Expansion of imports and government expenditure, along with private consumption and investment in buildings, seem to have played important roles in this recovery, despite mixed trends in non-oil exports and machinery investment (Figures 1 and 2). Treating government project wages as approximate indicators of manufacturing wages, relative wages and prices seem to have steadied in 2016 and began to reverse again in 2017, with real wages falling and the dollar and producer prices rising faster than the CPI (Figure 5).

U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 triggered significant declines in imports and all components of demand, as the rial plummeted against the dollar. Manufacturing output dropped between 2018 (Q2) and 2019 (Q3) by about 10 percent, but started to rebound despite continued downward trends in imports and all demand components. Manufacturing employment, which had been growing at the same rate as the economy-wide employment, accelerated and grew at a faster pace (Figure 3). These trends suggest an inward shift in domestic demand due to sharp increases in the prices of tradables. Notably, intensification of sanctions led to a decline in non-oil exports, despite the rial’s significant depreciation (Figures 1 and 5). It is likely that manufacturing firms adapted to the sanction environment, and many resumed growth based on domestic demand and resources. However, it is not clear whether this rebound has continued after 2020 (Q1), especially due to COVID-19.

In many ways, the aggregate trends in the 2012-2013 and 2018-2020 episodes of intensified sanctions are similar. However, the latter has come after a decade of declining investment and imports and a prolonged and more pronounced drop in private consumption (Figures 1 and 2). Another important difference is the allocation of credit in the wake of intensified sanctions: In 2012-2013, credit extended to manufacturing declined for about a year, but in 2018-2020, there was a substantial increase in the real amount of credit and the sector’s share in total credit (Figure 7). The government pursued this actively and included it in its 2018 annual budget law via incentives and requirements for allocation of bank credit [15]. Though this rechanneling did not lead to positive investment growth, it contributed to the working capital available to firms, thus helping them to continue operating and retaining more workers. According to the CBI, 68.3 percent of credit allocated to the manufacturing and mining sector in 2019 was for working capital [16]. This share was well over 70 percent in 2018 and almost 76 percent in spring and summer 2020 [17].

Finally, it is worthwhile to note the differences between trends in product prices and (government project) wages during the 2012-2013 and 2018-2020 sanction episodes. As Figure 5 shows, unlike in 2012- 2013, the real exchange rate continued to depreciate sharply, real wages dropped, and producer prices rose as U.S. sanctions tightened in 2018 and beyond. These wage and price movements may help partly explain both private consumption’s decline since 2018 and manufacturing output’s recent recovery observed in Figure 1. The contrasting wage and price behavior in the two episodes seem due to a number of factors, most notably much lower oil prices, more intense sanctions and a larger and continued drop in non-oil exports after 2018. A more constrained banking sector and lower investment and foreign exchange revenues in the years leading to 2018 compared to the pre-2012 situation may have also restricted the government’s policy options. There is more to explore regarding the differences between the two episodes, and definitive verdicts about the relevant factors await further study.

III. SANCTIONS AND FIRM ENTRY AND EXIT IN THE MANUFACTURING SECTOR

The aggregate value added derived from the SMF dataset (Figure 8) paints a picture for the late 2000s and early 2010s similar to the one based on macro data in Figure 1. Though there is some difference in the growth rates indicated by the two datasets for 2008, which could be partly due to the absence of firms with less than ten workers from the SMF dataset, the two sources more or less agree on what happened in 2009-2013. There was high growth during 2009-2011, then 5.5 percent decline in 2012, followed by a further drop of about 3 percent in 2013.

The SMF data allow us to go beyond aggregates and explore many details. One important issue is whether the decline in output under intensified sanctions was caused mainly by the exit of firms from the market or by shrinkage of output among surviving firms. Figure 8 depicts such a decomposition. The blue line represents the total value-added growth rate, and the thin orange line shows the growth rate of surviving firms in each period. The difference between the two curves is due to the net effects of firm entry and exit represented by the green and red lines, respectively. As shown, these effects were relatively small in 2009-2013, and though the effect of exits dominated entries, the net effect was insignificant compared to the fluctuations in aggregate growth.

This pattern does not quite apply to employment in manufacturing firms. As Figure 9 shows, the effect of firm exits on employment growth in the sector in the late 2000s was in the 1-2 percent range, which is not trivial. During 2012-2013, it was closer to 1 percent, which suggests that the intensification of sanctions did not increase loss of employment through firm exits. On the entry side, job creation by new firms was relatively small in the late 2000s and declined further after 2009. This implies that the gains in employment at the time must have come about by changes in the workforces of existing firms. The graphs in Figures 8 and 9 further indicate that employment was far more resilient in manufacturing than value added. As sanctions intensified in 2012, it fell much less than value added. One reason for the smaller decline in employment is likely to be Iranian labor laws that make it difficult for companies to lay off workers. However, government pressure on firms, especially the larger ones, may also be at work. Interestingly, in 2013, when real wages had substantially diminished and anticipation of sanctions relief started to grow, the sector’s workforce quickly expanded well before its value-added showed signs of recovery.

Growth rate of manufacturing firms’ total capital stock during 2012-2013 sanctions has similarities with that of value added, though the capital stock was growing quite fast in 2008, when value added and employment declined (Figure 10). This provides corroborating evidence for the earlier conjecture that capital-labor substitution had been an important feature of manufacturing dynamics in the 2000s. The net role of entry and exit is again rather small. However, gross entry and exit effects were somewhat more important for capital stock than for value added, and the entry effect became negligible after UN sanctions went into effect.

Figure 11’s breakdown of capital stock into its three main components – machinery, buildings and land – shows that machinery had been fastest growing in 2000s, followed by buildings. The growth rate of capital formation in the form of machinery did not turn too negative during 2012-2013. Investment in buildings seems to have declined more. The growth rate of land capital was negative prior to 2010 and became considerably positive in 2011, before reversing significantly when sanctions struck. The role of entry and exit had been important for all three components in 2008, but was so in 2012-2013 only for buildings investment. Interestingly, exiters in that period seem to have depended on building investment much more than survivors. That suggests many firms may have entered manufacturing before 2010 to take advantage of real estate investment opportunities and, perhaps, to access the concessional credit available to the sector [18]. Many of them exited when the real estate market peaked and started to stagnate.

A major difference exists between macro and micro data when it comes to non-oil exports. In contrast to CBI data that suggest a sharp rise in such exports in 2012 followed by a decline after mid-2013, SMF data indicate that when UN sanctions were imposed, manufacturing firms’ exports initially contracted sharply and then partially recovered (Figure 12). Some firms possibly had continued to export, but kept their foreign exchange revenues abroad and did not declare them. Once it became clear in 2013 that sanctions might be eased, they were more inclined to declare those revenues. Another possibility is that it may have taken a bit of time for some exporters to arrange to use their dollar revenues without running into problems of banking sanctions or government foreign exchange controls. Such arrangements often involved using the dollars abroad to pay directly for imports. Though exporters used some export revenues to pay for their own imported inputs, for the rest they had to find and contract with appropriate buyers. The matching process and securing of deals may have taken time that would in turn have delayed declaration of export revenues. Another remarkable fact reflected in Figure 12 is that entry and exit played virtually no role in export changes. That was probably because exporting firms tend to be more productive and successful — thus very unlikely to exit the market — and very few of them enter each year [19]. However, if attention is restricted to the group of firms that ever exported during 2003-2013 and entry and exit are defined as becoming an exporter and stopping to export, respectively, then a decomposition similar to that in Figure 12 shows that exit had been lowered export growth by about 3.1 to 5.9 percent. Entry, on the other hand, had added 0.8 to 2.6 percent to that growth, with the highest contribution (2.6 percent or almost a quarter of total real export growth) being reached by a wide margin in 2013.

IV. DIFFERENTIAL IMPACTS OF SANCTIONS ON MANUFACTURING INDUSTRIES

To shed some light on the role of industry characteristics in manufacturing firms’ responses to sanctions, we calculate the average shares of two-digit industries during 2008-2011 and 2012-2013 in the total value added of firms in the SMF dataset. Table 2 reports the results and shows the difference between the periods. It is important to note first that Iran’s manufacturing is dominated by five industries: “Food Products,” “Chemicals” (essentially petrochemicals), “Other Non-Metallic Mineral Products,” “Basic Metals” and “Motor Vehicles.” Most other sectors have value added shares below 1 percent.

The second remarkable fact is the pattern of industrial restructuring associated with the intensification of sanctions: The most notable shift in value added shares is a reallocation from “Motor Vehicles” to “Chemicals,” and to some extent to “Basic Metals” and “Food Products.” Almost all other industries also lost shares to these. One way to interpret this pattern is to note that the shift has been away from industries dependent more on imported inputs and technology and toward industries heavily reliant on domestic resources that could benefit from the growing potential of Iran’s natural export markets in central and southwest Asia. This is clear for “Chemicals” and “Basic Metals,” which rely on fossil fuel extraction and mining. The government also ensured that the chemical/petrochemical industry received its key input — natural gas — at very low cost. The shift to “Food Products” was weaker, probably because that industry depended more on local resources with low supply elasticity (especially agricultural land) and on imported inputs.

Export market factors had generally small to moderate roles in the 2012-2013 restructuring of manufacturing value added, as can be seen in Tables 3 and 4. According to Table 3, well over two-thirds of manufacturing exports come from the Chemicals industry, which prior to 2012 exported about 40 percent of its production (Table 4). After sanctions were intensified in 2012, Chemical exports were negatively affected: their value as share of total manufacturing exports dropped to 65.4 and as share of the industry’s production to 32 percent. It seems that sanctions may have made it more difficult for Chemicals firms to export. It is also possible that they may have under-reported exports to keep foreign exchange revenues abroad. Domestic demand, however, expanded strongly and helped total Chemicals production to rise. Motor Vehicles was another industry to lose export share in 2012-2013, but its production contracted by about 40 percent over the two years, as domestic sales also dropped due to input constraints and weak demand. In a number of other industries where production shrank, such as Electrical Machinery and Other Transport Equipment, diminished domestic sales were again a major factor, but exports did even worse. However, several industries benefitted from export expansion even though their domestic sales were weak (eg, Food Products, Leather, and Fabricated Metals). Overall, exports helped maintain demand for many manufactured products. As the last row of Table 4 shows, the share of exports in total manufacturing production increased during 2012-2013 compared to 2008-2011. This is in line with the effects of the rial’s devaluation [20].

The reallocation pattern discussed above took place mainly among large firms. For medium and small firms, the changes in the value-added shares between 2008-2011 and 2012-2013 were rather small, while for large firms they were even greater than those observed in Table 2. There also was little net reallocation of the value-added shares among firms in different size categories (Table 5). However, this does not mean that mobility of firms between different size groups has been trivial. Such mobility was discernible, but, transitions were both ways, and around the time when UN sanctions were imposed, the net effects turned out to be very small.

Similar exercises to examine the reallocation of production factors (labor, capital, and land) across industries did not find much evidence of change, since those factors are not very mobile. Even for labor, which tends to be more mobile than physical capital, the shift in employment was quite muted.

Limited reallocation of labor across industries in the face of the major decline in real wages meant that the labor shares in value added must have generally declined among manufacturing firms. This is confirmed in Table 6, which shows the labor shares in value added in 2008-2011 and 2012-2013, as well as the difference in those periods. However, the table also reveals a substantial variation in labor share changes across industries that has a notable pattern: industries where value added shrank relatively less compared to the baseline situation in 2008-2011 experienced larger drops in labor shares in 2012-2013. This can be seen most clearly in the “Motor Vehicles” industry, where value added dropped most, and the average labor share almost doubled (from 13 to 25 percent). On the other side of the spectrum is “Chemicals,” where value added increased substantially, and labor share dropped by a third (8.5 to 5.4 percent). A key reason is the constraints that especially larger firms face in shedding labor and keeping wages low due to labor laws and political pressure. As a result, the wage bill is not very responsive to a firm’s conditions, and when value added drops, labor share rises.

V. SANCTIONS AND SCALE OF PRODUCTION ACROSS FIRM SIZES AND INDUSTRIES

As seen, contraction of the manufacturing sector in 2012-2013 was largely due to the decline of activity among surviving firms rather than firm exit. That is, the scale of production must have generally declined. The issue of production scale is important, because fixed costs probably did not decline when sanctions hit. As a result, average production cost must have increased, especially for firms subject to economies of scale. This may have compounded the consequences of supply and demand shocks from sanctions, since the unit cost increase could push up product prices and further choke demand and production [21]. Here we examine the patterns of scale changes among manufacturing firms of different sizes and industries.

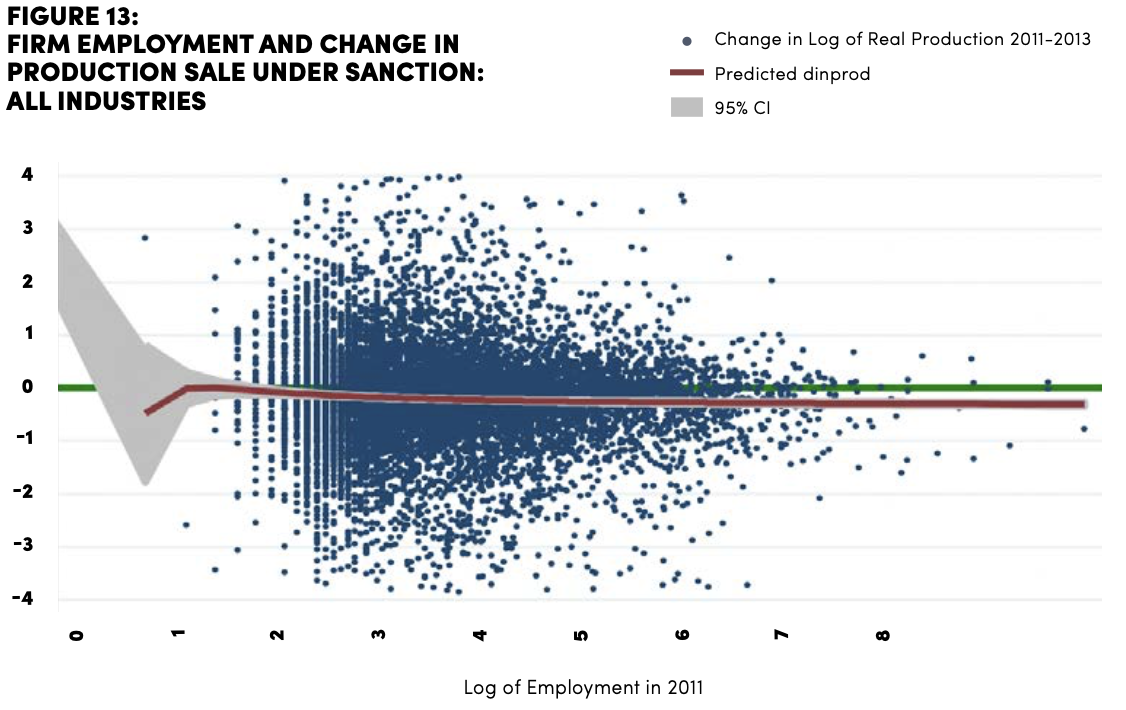

We begin with all firms in the dataset and measure their real production level change between 2011 and 2013. Naturally, this applies only to the sector’s surviving firms. However, as argued above, eliminating entrants and exiters should not affect the results significantly. Next, in Figure 13, we plot the scale change measure against the log of employment across firms in 2011. The plot also includes the predicted value of the change based on a fractional polynomial regression, along with its confidence interval. For all firm sizes above 15 workers, the predicted value is below zero, indicating that on average firms have shrank by 10 to 25 percent, with larger firms experiencing greater contraction. Median firms in various size categories have experienced similar production declines. These findings may help explain the sharp drop in average TFP observed in Figure 4.

As one may expect based on reallocation of value added discussed above, the extent of scale reduction varies greatly across industries. The most significant declines are in “Motor Vehicles,” “Other Transport” and “Furniture.” Figure 14 shows scale change vs. employment for the “Motor Vehicle” industry as an example. Its average scale reduction directly grows with firm size and ranges from 30 percent for small firms to almost 80 percent for the largest. However, there is no detectable change in the average production scale of firms in the “Textiles,” “Wood Products,” “Paper Products,” “Publishing and Printing,” “Chemical Products,” “Fabricated Metal Products,” “Computing Machinery,” “Communication Equipment,” and “Medical Instruments” industries. Figure 14 shows the situation for “Chemical Products” as an example. Some other industries come close to maintaining their average scales (eg, “Food Products”). All others experienced significant average scale reductions at least for some firm-size ranges. Even in “Basic Metals,” which expanded its share of manufacturing value added, small and medium size firms experienced, on average, some scale reductions.

VI. CONCLUSION

Economic sanctions have been extremely costly for Iran’s manufacturing firms. In most industries, the majority of firms have experienced significant cost increases and production scale reductions as a consequence of supply constraints and demand contractions. Imports have been in short supply, and even non-oil exports that should have become more profitable as a result of currency depreciation have stagnated as sanctions have continued. As a result, manufacturing firms have reduced investments, further exacerbating the demand problem each faces. The intensified sanctions since 2018 seem to have been more devastating to the economy and livelihoods than those of 2012-2013, as evidenced by sharply lower real wages and declining consumption. However, in some important ways Iranian manufacturing firms have proven resilient. Exit rates have not been particularly high, and manufacturing employment has actually increased during both episodes. The firms seem to have adapted to sanction conditions, particularly by shifting toward products that rely more on domestic resources and less on imports and foreign technology. They have even gradually found ways to grow.

ENDNOTES

Emma Ashford, “Not-So-Smart Sanctions: The Failure of Western Restrictions against Russia”, Foreign Affairs, January/February2016; Leonid Bershidsky, “Some Sanctioned Russian Firms Thrive on Adversity”, Bloomberg Opinion, 8 May 2018; Daniel P. Ahn and Rodney D. Ludema, “The Sword and the Shield: The Economics of Targeted Sanctions”, CESifo Working Papers no. 7620 (2019); and “Measur- ing Smartness: The Economic Impact of Targeted Sanctions against Russia”, in Tibor Besedes and Volker Nitsch (eds.), Disrupted Economic Relationships: Disasters, Sanctions, Dissolutions, (Cambridge 2019); M.J. Draca, J. Garred, L. Stickland and N. Warrinnier, “On Target? Sanctions and the Economic Interests of Elite Policymakers in Iran”, Working Paper, University of Warwick (2019).

Gabriel Felbermayr, Constantinos Syropoulos, Erdal Yalcin and Yoto V. Yotov, “On the Heterogeneous Effects of Sanctions on Trade and Welfare: Evidence from the Sanctions on Iran and a New Database,” School of Economics Working Paper Series 2020-4, LeBow College of Business, Drexel University.

For example, the exercise implies that the sanctions during 2012-2013 must have increased motor vehicle production, while in fact that was the hardest hit industry at the time.

Draca et al, op. cit.; Saeed Ghasseminejad and Mohammad R. Jahan-Parvar. “The Impact of Financial Sanctions: The Case of Iran 2011-2016”, International Finance Discussion Papers 1281 (2020). https://doi.org/10.17016/ IFDP.2020.1281.

The “semi-state” sector refers to firms that the authors call “politically connected” (eg, owned by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and its affiliated companies).

Another problem with these studies is that the political connections of Iranian firms are very complex, and the data used in the papers are not public, so the semi-state designation of firms cannot be verified.

7. For the timing of sanctions’ intensity, the study relies on the dataset compiled by Gabriel Felbermayr, Constantinos Syropoulos, Erdal Yalcin and Yoto V. Yotov, “The Global Sanctions Data Base”, School of Economics Working Paper Series 2020-2, LeBow College of Business, Drexel University (2020).

8. The SCI also produces macro-economic data, but it includes trend changes that are sometimes difficult to reconcile with other sources of information.

9. The SMF dataset includes the “Coke, Refined Petroleum Products and Nuclear Fuel” industry under manufacturing. Since the value of that industry’s production is mostly due to natural resources, it is excluded from this paper’s calculation and analysis.

10. See also Mehran Behnia, Arash Alavian, and Amin Fareghbal, “Labor Market Report”, Institute for Management and Planning Studies (2015). (In Persian), and Institute for Management and Planning Studies (IMPS), Report on a Study of Economic Sectors, Vol. 2: Manufacturing (2016). (In Persian).

11. This is reflected in the downward trend of the CPI-deflated manufacturing producer price index in Figure 5.

12. Figure 5 shows the wage rates of skilled electricians and unskilled workers employed in the government’s development projects in Tehran Province as examples of wage trends.

13. Part of the changes in the manufacturing wage index could be due to shifts in the composition of skills of manufacturing workers. However, according to worker skill data in the SMF dataset, this did not play much of a role in real wage changes during 2009-2013.

14. For further exploration of this issue, see Section IV below.

15. See the Budget Law for Iranian Year 1397, Article 18, Clause A, https://iranbudget.org/blog/fi- nalbg-97/.

16. CBI, “Credit Extended by All Banks by Sector and Purpose in 12 Months of Year 1398”, (2020). https://www.cbi.ir/page/20091. aspx.

17. CBI, “Credit Extended by All Banks by Sector and Purpose in First Six Months of Year 1399”, (2020). https://www.cbi.ir/ page/20672.aspx.

18. This seems to be a general pattern for many industrial projects in Iran, where the apparent goal of investments is to profit from land property appreciation rather than value generated through industrial production. In some cases, the government gives land to investors to create jobs, but they are more interested in land value growth. For example, in a 2015 interview (here), the managing director of the Small Businesses and Industrial Parks Organization said 16,000 hectares of land with infrastructure in 752 industrial areas had been made available to investors, but some made little effort to invest.

19. Sanctions created pressure on some foreign-owned firms to leave Iran, but the pace of exit was very slow, as the UN resolutions allowed them to fulfill existing projects and commitments.

20. It also reflects the emergence of regional markets examined in Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, “Resistance is Simple, Resilience is Complex: Sanctions and the Composition of Iranian Trade”, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Working paper (2020).

21. Hadi Salehi Esfahani and Kowsar Yousefi, “The Impact of Intensified International Sanctions on Iran’s Manufacturing Sector, 2012-2013,” Working Paper, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2020), explore this issue and argue that the scale effects must have played an important role in reducing total factor productivity during sanctions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hadi Salehi Esfahani is a Professor at the Departments of Economics and Business Administration at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance and a Board member of the Economic Research Forum for the Arab Countries, Iran & Turkey. He is a founding member of the International Iranian Economic Association and has served as the Director of the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Illinois and as the President of Middle East Economic Association. He has also worked for the World Bank as a policy research economist and as a consultant. He holds a B.Sc. in engineering from the University of Tehran and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of California at Berkeley. His research focuses on the role of politics and governance in economic policy formation, especially in fiscal, labor, and trade areas. His main area of specialization is the political economy of development in the Middle East and North Africa region. His articles have appeared in journals such as The Economic Journal, Review of Economics and Statistics, Journal of Development Economics, International Economic Review, Oxford Economic Review, World Development, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, and Iranian Studies.

The SAIS Initiative for Research on Contemporary Iran

Johns Hopkins University Washington, DC

Copyright 2020 All rights reserved